Blockchain Privacy Mechanisms

This post will give you a brief overview of the major blockchain privacy mechanisms that are implemented in cryptocurrencies today and show you how the Lelantus protocol used in Firo and the upcoming Lelantus Spark protocol stacks up. This is a living document that would be updated from time to time with recent developments.

Blockchain privacy is particularly tricky to achieve as public blockchains are designed so that all transactions are transparent and coin amounts are public. This is because everyone has to be able to validate the state of the chain and balances. Balancing privacy with the requirement for public verifiability in blockchains is not a trivial problem.

To understand the innovation behind Lelantus and Lelantus Spark, we need to also understand how other privacy systems work.

Cryptocurrency Tumblers and CoinJoin

As used in: Dash, Decred, Bitcoin Cash, Bitcoin mixers

Pros:

- Works on top of most cryptocurrencies without the need for specific consensus rules

- Relatively simple to implement

- Transactions are regular transactions introducing no additional overhead

Cons:

- Amounts are still completely visible

- Anonymity sets are generally low and reliant on the number of mixers

- Coins that are mixed can be ‘flagged’ as going through a coin mixer.

- Needs time for mixes to happen

- Requires mixers to be online

- Difficult to use correctly and cumbersome requiring careful UTXO management

- Increases blockchain bloat with many transactions required to do mixes

- Earlier implementations involve trust in a third party mixer

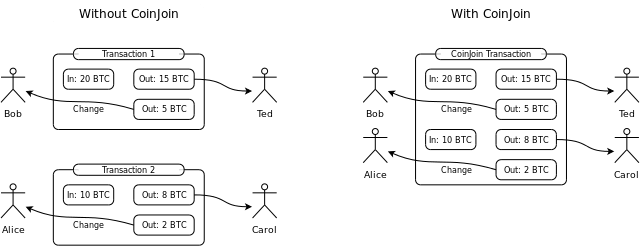

One of the first methods people sought to achieve this was through the use of cryptocurrency tumblers. These work based on the principle of mixing funds with others by sending your coins to other people and then giving their coins to you. An easy way to visualize this is a group of people each putting the same number of coins into a pot, mixing it up and then each taking out the same amount of coins. The idea is that it is now hard to prove whose coin formerly belonged to whom thus providing plausible deniability. Early tumblers required you to trust the tumbler not to steal your coins or log how the mixes are done.

CoinJoin is an improvement of this mixing idea and removes the possibility for the tumbler to steal the coins. It is used in Dash and also forms the basis of many coin tumblers. However, there are many drawbacks to the system.

- You need to trust the tumbler for your anonymity as the mixer can log identifiable information and knows how the mix is happening along with each user’s input address and the address they are receiving coins to. This issue can be avoided by using blind digital signatures but then the anonymity of CoinJoin relies strongly on the possibility to connect to the tumbler in an anonymous manner, e.g., via the Tor network.

- It requires people involved in the mixing to be online for a mixing transaction to happen. If no one wants to mix for the right denominations, your mix can be delayed.

- The anonymity is limited by the amount of people you mix with. A typical round of Dash’s Privatesend mixing involves 3 participants only though this can be repeated.

- Even with multiple rounds of CoinJoin mixing, recent research shows that a user’s wallet can be identified if they are not careful with browser cookies when making payments because mixing only obscures the transaction links between addresses but does not break them completely.

- It is easy to disrupt a run of CoinJoin and delay the completion of the transaction for the other participants.

What’s more, Dash’s implementation, previously called PrivateSend, is susceptible to cluster intersection attacks.

Other improvements such as CoinShuffle and CoinShuffle++ as used in Decred added further protection from the tumbler stealing coins but are still subject to the other drawbacks of CoinJoin, namely a limited anonymity set and the requirement that participants are online. Coinshuffle systems cannot perform a mix with more than 50 users. CoinShuffle systems are also vulnerable to DoS attacks where a user who joins the mix and aborts can disrupt the mixing process for other users.

The state of the art mixers such as Tumblebit and CashFusion further improve over this allowing more users to mix and faster mixing speeds while preventing the tumbler from knowing how mixes are made. CashFusion also doesn’t require the use of fixed denominations.

The main benefit of mixer type schemes is that they are relatively simple and work on top of the cryptocurrency without the need to use specific consensus rules. They also preserve full supply auditability as all amounts are not hidden. However even state of the art mixer systems do not solve the limitations of coin mixer systems which are: the need for specialized mixer servers to be hosted, amounts are fully visible, others need to be online to mix and perhaps the biggest one is that they require you to carefully handle your UTXOs to avoid mixing and can be quite cumbersome to use for multiple transactions.

Coins that go through mixers are also often ‘flagged’ with a higher risk meaning that your coins can be tainted just by going through this process. This can be exacerbated if coins that are tainted from illicit activity are mixed together with yours further making your coins difficult to use on exchanges. The freezing of coins connected to CoinJoins have been happening on a regular basis:

- Binance Returns Frozen BTC After User ‘Promises’ Not to Use CoinJoin

- BlockFi considered CoinJoin as ‘prohibited activities

- Another Crypto Exchange Discourages the Use of Bitcoin Mixing Services

With appropriate precautions and correct use, CoinJoin and similar systems can provide some privacy to defend against trivial chain analysis but shouldn’t be considered as a sufficient privacy solution nor does it solve the issue of fungibility given that CoinJoined coins are often treated differently.

Even Wasabi wallet’s creator admits that it is a temporary hack and that without confidential transactions, privacy will be priced out of Bitcoin’s main chain. This makes sense given the large number of transactions required to do CoinJoin along with the additional transactions required to break amounts into fixed denominations.

CryptoNote, Ring Signatures, RingCT

As used in: Monero, Particl, Zano

Pros:

- No need for a mixer and mixing is done automatically

- Can be implemented with privacy on by default

- Anonymity increases as time passes as outputs become the new inputs of new mixes

- Hides transaction amounts when implemented with RingCT

- Well understood cryptography

Cons:

- Does not break transaction links, merely obscures them, hence a ‘decoy’ model.

- Selecting the right decoys can be tricky and incorrect input selection algorithms can lead to loss of privacy

- Low anonymity set per transaction due to practically limited ring sizes

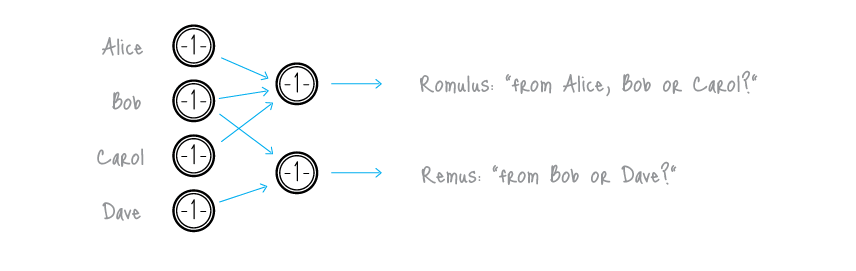

The next anonymity scheme we will explore is ring signatures as used in CryptoNote currencies such as Monero which significantly improves anonymity over regular mixer type schemes. A ring signature works by proving someone signed the transaction from a group of people without revealing which person it was. One common proposed use case of ring signatures is for it to be used to provide an anonymous signature from a “high-ranking White House official” without revealing which official signed the message.

CryptoNote uses ring signatures in a way whereby a user can craft a transaction and use the outputs of other similar transactions on the blockchain automatically to form the inputs to a ring signature transaction so that it is unclear which input belongs to the person doing the transaction. It does this automatically without requiring other users to specify that they wish to mix and does not need to wait for other people to provide funds since it’s just scanning the blockchain for those outputs to use. As there is no mixer, there’s no mixer you need to trust.

CryptoNote/ring signatures when combined with confidential transactions also hide amounts and used together they’re called Ring Confidential Transactions (RingCT). Most implementations using this privacy mechanism also now use RingCT after Monero implemented it in 2017.

Another great feature of this protocol is that most implementations have mandatory stealth addressing which solve the address re-use problem and protects the receiver’s privacy.

RingCT currencies also have limitations concerning practical ring size (the number of other outputs you are taking) as the size of a transaction grows linearly as the ring size increases. This is why Monero has a relatively small ring size of 11 though it is set to increase this to 16 in an upcoming hard fork. This means on a per transaction basis, the anonymity is limited by the number of inputs in the ring. While the possibilities start to fan out increasing the practical anonymity set, the real transaction link is still somewhere in there hiding among the decoys and there are methods to narrow the range of possibilities down such as theorized Flashlight, Overseer and Tainted Dust attacks.

Also, security researchers have on numerous occasions found numerous ways to make educated guesses as to which transaction is the real one by using statistical analysis and the age of the inputs. Picking the right decoys to form your ring can be tricky. For example, a 2017 study demonstrated that in any mix of one real coin and a set of fake coins bundled up in a transaction, the real one is very likely to have been the most recent coin to have moved prior to that transaction due to the way the decoy selection algorithm picked its inputs. That timing analysis correctly identified the real coin more than 90 percent of the time, virtually nullifying Monero’s privacy safeguards.

To combat this, the Monero developers have changed the algorithm on how the wallet picks its mix-ins several times and have also increased the number of mix-ins. Despite such changes, while improving resistance against previous methods, they still can be narrowed down as highlighted in the 2018 version of the same study and even in 2021, there remain known drawbacks.

More recently in July 2021, another error of implementation in decoy selection allowed users who spend their funds within ~20 minutes after receiving funds to have the true spend identified. This issue has been since rectified but does not protect users who had already done this prior to the fix.

A recent submission to Monero’s Vulnerability Response Process has also indicated that even with the most recent fixes, there may be still issues with the current decoy selection algorithm though this has yet to be widely verified and is still an issue of active research.

In short, the strength of the decoy selection algorithm has been a constant weakness in RingCT type of systems and fixing it conclusively has proven challenging though it can be partially mitigated with large increases in ring size.

Another issue with decoy based systems are ‘flooding’ attacks where an attacker can flood the network with their own transactions to remove mixins from transaction inputs. This was documented in the paper FloodXMR which shows that an attack can be mounted by flooding transactions to remove mixins from transaction inputs. There is however ongoing debate as to the cost and efficiency of such techniques as the authors of that paper made several wrong assumptions on fees.

Another criticism of RingCT is that if there’s a weakness in its ring signature implementation or a reasonably powerful quantum computer becomes feasible, the entire blockchain history is deanonymized and retroactively exposed. This cannot be fixed after the fact. In fact, a flawed implementation in a CryptoNote currency called ShadowCash allowed for its blockchain to be deanonymized in its entirety. However, a practical quantum computer is still quite some time off, and it boils down to whether several-year-old transactions data are still valuable. For this data to be useful, it will most likely need to be combined with external data.

In RingCT, someone who breaks the discrete logarithm that underpins RingCT can forge coins without anyone knowing it. That being said, for now this is only a theoretical possibility as the discrete logarithm problem is widely used in cryptography and it is expected that discrete logarithms will remain viable until the age of quantum computing.

Privacy coins ultimately need to hide amounts transacted to provide the highest level of privacy and the trade off is the loss of supply auditability. RingCT in particular requires mandatory privacy and full hidden amounts to achieve high levels of privacy. A lack of supply auditability can complicate detecting hidden inflation. A bug in Cryptonote that allowed unlimited inflation was indeed discovered but was patched before anyone could take advantage of it. A nuanced argument on supply auditability in privacy enhancing cryptocurrencies can be found in Riccardo Spagni’s presentation On Privacy Enhancing Currencies & Supply Auditability.

Despite these drawbacks, RingCT has proven itself to be one of the better and well-reviewed privacy technologies out there that is still evolving and improving to deal with new threats and advancements.

It is worth noting that Monero Research Labs are looking into alternative privacy protocols to help scale their ring sizes such as Lelantus Spark and Seraphis to increase its effective anonymity set and complicate statistical analysis.

Lelantus v1/v2

As used in: Firo (activated Lelantus v1 from January 2021)

Pros:

- No need for a mixer

- High anonymity sets up to around 65,000.

- Uses well-researched cryptography and only requiring DDH cryptographic assumptions

- Small proof sizes of around ~1.5 kB per proof

- No trusted setup

- Doesn’t use fixed denominations

- Can do direct anonymous payments without having to convert to base coin (for Lelantus v2).

- Efficient batch verification

Cons:

- Anonymity sets cannot scale into the millions without cryptographic breakthrough

- Lelantus v1 still does not fully hide amounts as only source and change amounts are hidden (Lelantus v2 fully hides amounts)

- No stealth addressing support meaning users are still recommended to supply fresh addresses

- Lelantus v1/v2 balance security lacks a formal security proof and is challenging to formulate one

Lelantus is a creation of Firo’s cryptographer Aram Jivanyan as part of our continuous efforts to improve our privacy protocol and its full paper is available to read here.

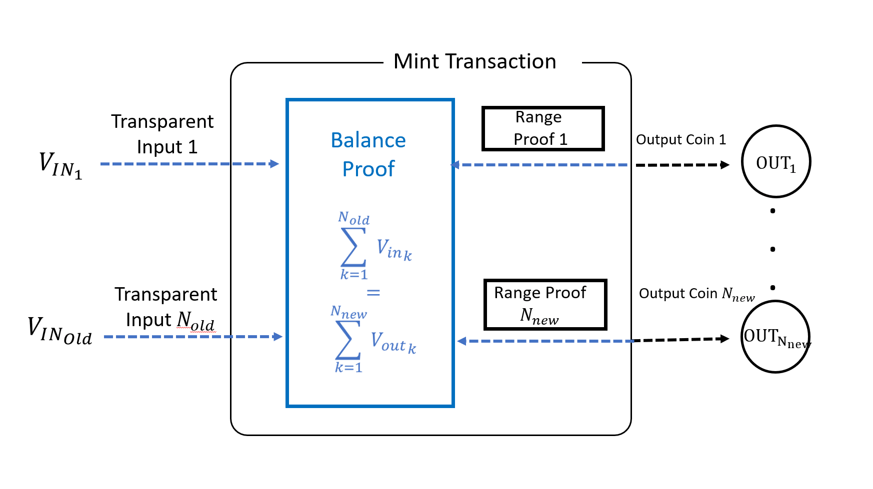

Lelantus v1 uses a burn and redeem model that was first pioneered by the Zerocoin protocol whereby coins are burnt and then later redeemed for brand new ones that do not contain transaction history nor an identifiable source.

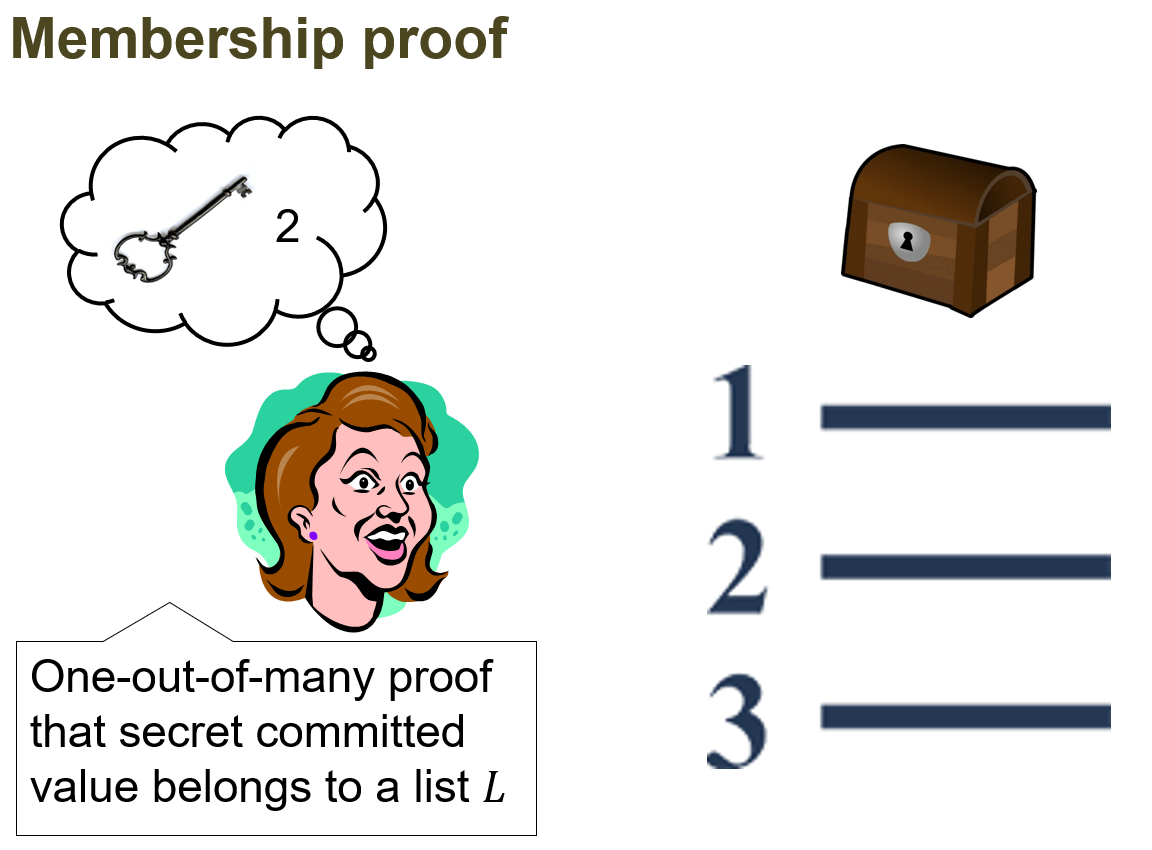

A simple way to imagine this is throwing coins into a black box. Those that throw coins into the black box retain a special receipt that allows them to prove that they did throw coins in the black box without having to show exactly which coins were burnt. This receipt or proof is built from a trustless zero-knowledge proof called one-out-of-many proofs aka Groth-Bootle proofs that does not require trusted setup. This construction was further optimized in the paper Short Accountable Ring Signatures based on DDH (Jonathan Bootle, Andrew Cerulli, Pyrros Chaidos, Essam Ghadafi, Jens Groth and Christophe Petit)..

Previous burn and redeem schemes such as Zerocoin and Sigma (which were also previously used in Zcoin) required users to burn and redeem in fixed denominations and also did not allow partial redemptions. For example if I burnt 10 coins but wanted to spend 3 of them, I would need to redeem 10 fully, send the three and then reburn the 7. This is inefficient and involves several steps.

Lelantus allows burns and redemptions of arbitrary amounts along with the ability to do partial redemptions. For e.g. this means I can burn 9.23 coins and can redeem 1.7 coins partially and have the change amount hidden.

This makes it much harder to do analysis based on time or amount correlation. It also greatly simplifies the handling of UTXOs since there are no leftover dust amounts that a user would need to keep separately.

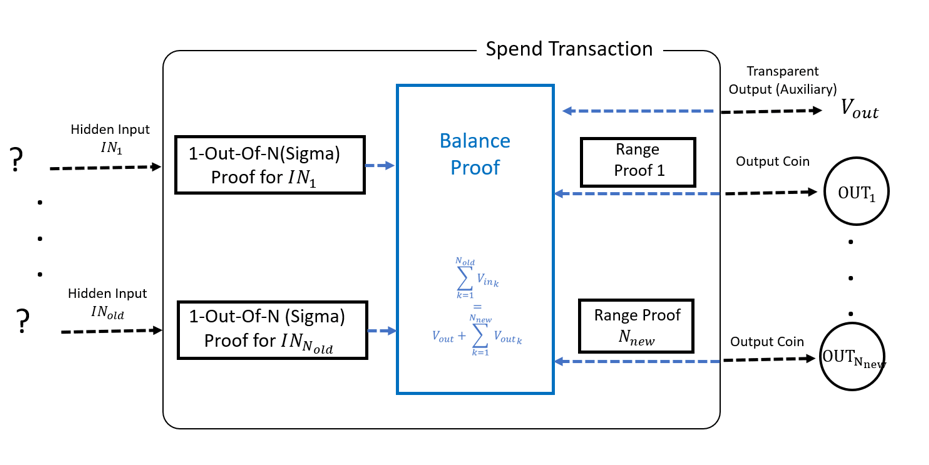

Lelantus hides the transaction amounts of the inputs and also the change amount. It achieves this by utilizing double-blinded commitments and a modification of bulletproofs to hide transaction amounts.

Lelantus v2 expands Lelantus v1 functionality and allows for direct anonymous payments and fully hides amounts. This means users don’t need to redeem the coins which expose its amounts but instead can pass these coins to a third party without ever revealing the amount to third parties.

A limitation of Lelantus v1/v2 is due to the usage of Groth-Bootle proofs, anonymity sets are limited to the high thousands before verification and proving performance become unacceptable. This anonymity set is still magnitudes higher compared to almost all other privacy mechanisms with the exception of Zerocash with its own set of trade offs (trusted setup, complicated construction, etc) which we will explore further below.

Lelantus also lacks stealth addressing support meaning that while users cannot see the source or amounts or when funds are spent, it can tell that a particular address has received some funds which reveals timing information.

Our work in Lelantus has also revived interest in the use of Groth-Bootle proofs and has lead to a new breed of privacy protocols such as Triptych (Monero Research Labs), Lelantus-MW (Beam) and Lelantus-CLA (Beam).

Lelantus Spark

As used in: Firo (to go live in 2022)

Pros:

- Retains all the pros of Lelantus v1/v2 using well researched cryptography, no trusted setup and having efficient batch verification

- Full support of stealth addressing, efficient multi/threshold signatures and view key functionality via Spark addresses

- Modular design which allows easier upgrade of components

- Unlike Lelantus v1/v2 a security proof for the balance is available

- Relatively simple cryptographic design compared to circuit-based zero-knowledge proof systems making it easier to implement and less room for error.

Cons:

- Difficult to scale past anonymity sets larger than 100,000 without cryptographic breakthrough, huge optimizations or replacement of underlying Groth-Bootle proofs.

- Verification of proofs are still slower than Groth16 zkSNARKs but are mitigated with efficient batch verification

Lelantus Spark is the work of Firo’s research team and is slated to be launched on Firo’s mainnet in 2022. Lelantus Spark builds on the work of Lelantus v1/v2, and like Lelantus v2 hides the sender and fully hides amounts but greatly improves recipient privacy with the introduction of Spark addresses. The efficient and trustless Groth-Bootle one-out-of-many proofs still form the foundation of Spark as it did with Lelantus v1/v2 and Sigma.

Spark addresses work similarly to stealth addresses by allowing people to publicly share their address without it being searchable on the blockchain. Spark addresses instead automatically allows senders to generate one-time addresses on behalf of the recipient, which then designates who can spend the funds in the transaction. Additionally, third parties then are unable to easily link the recipient’s wallet address to a transaction on the blockchain without the assistance of additional external information.

Spark addresses also has full view key support meaning it can track both incoming and outgoing funds should you choose to reveal it. In comparison, Monero’s stealth addresses only support incoming view keys making it hard to disclose balances even if you wanted to. Spark addresses also has efficient multi-sig and threshold signature support.

The primary advantage of Spark and Lelantus based systems are its simple design and reliance on standard cryptographic assumptions while offering very high anonymity sets along with flexible addressing system. This offers a real alternative to those who may not be comfortable with more complicated constructions where there are much more moving parts, use more experimental math or require a trusted setup.

Also as all amounts would be hidden with Spark, supply isn’t transparently auditable and rely on zero knowledge proofs to preserve supply like in RingCT and Zerocash. A nuanced argument on supply auditability in privacy enhancing cryptocurrencies can be found in Riccardo Spagni’s presentation On Privacy Enhancing Currencies & Supply Auditability.

The biggest criticism that can be said of Spark is because of its current reliance on Groth-Bootle proofs, the anonymity set still cannot be made a global anonymity set and verification performance is still lower than Groth16 zkSNARKs used in the Zerocash protocol.

While practical anonymity might be in practice equivalent, we are keeping a close eye on improvements in membership proofs that might replace Groth-Bootle to allow Spark to have global anonymity sets.

Spark’s cryptography has completed two independent audits and has full security proofs for its design.

Seraphis, a privacy framework in consideration by Monero to replace RingCT shares many similarities with Lelantus Spark and derives many key parts of its design from our work such as the use of one-out-of-many proofs and our approach to addressing. However its proposed implementation would still use a decoy model and increase its ring size rather than Firo’s use of pools of anonymity combined with our sliding window approach.

Zerocash

As used in: Zcash, PirateChain, Horizen, Komodo, PIVX

Pros:

- Theoretically the best anonymity set encompassing all coins minted and breaks transaction links between addresses.

- Proof sizes are small and fast to verify

- Hides transaction amounts

Cons:

- Private transactions are computationally intensive (though much improved with Sapling upgrade)

- Complicated trusted setup that has to be arranged by the team

- Incorrect implementation or leakage of trusted setup parameters can lead to forgery of coins.

- Uses relatively new cryptography and based on less standard cryptographic assumptions (KEA)

- Complicated construction and difficult to understand in full meaning that only a handful of people can grasp the cryptography and code and may be prone to errors.

One of the leading privacy schemes is the Zerocash protocol as used in ZCash. Zerocash builds on the work of Zerocoin and seeks to address the shortcomings of Zerocoin. With Zerocash and its use of zkSNARKs, proof sizes are small and are very fast to verify. Furthermore, all transaction amounts are hidden and there is no longer a need to use fixed denominations when doing a minting transaction. Zerocash also allows people to transfer anonymous coins to each other without the need to convert back into the base coin. Its anonymity set is also the largest among all previous anonymity schemes involving all minted coins regardless of the denomination on the blockchain.

Like its predecessor Zerocoin, Zerocash requires a trusted setup, but Zerocash’s setup is much more complicated. For its initial deployment of Sprout, Zcash utilized a multi-party ceremony involving six people set up in a way that the only way these parameters could be leaked is if all six in the ceremony colluded to retain the keys. In other words, you have to trust all of these six people that they destroyed the initial parameters and also that the ceremony was carried out correctly. Weaknesses and flaws in the initial setup led to Zcash organizing a new trusted setup ceremony that involved 88 participants and addressed other weaknesses in the original Sprout ceremony.

If there is a bug in the code, or a cryptographic flaw or an issue with the multi-party trusted setup, an attacker can possibly generate unlimited Zcash and this additional supply cannot be detected.

Zcash actually had one of these bugs live on its Sprout mainnet from launch until the 28 October 2018, a period of two years, before it was patched in Sapling arising from a cryptographic flaw. There is no way to tell whether this bug was taken advantage of prior to being patched and there was a gap of 8 months from the time of finding the bug till it was patched. This wasn’t the first time such a bug was discovered. Zerocash early in its development also had the InternalH Collision Vulnerability which would have allowed forging of coins as well. Although this bug never made it to production, it highlights the potential risks.

BTCP, a fork-merge of Zcash and Bitcoin also suffered hidden inflation which went undetected for over almost ten months. This inflation was only detected by examining the UTXO import process when they were importing over the Bitcoin UTXOs. This wasn’t due to a flaw in the cryptography but rather a covert premine.

Another trade-off is the use of new experimental cryptography. Unlike well established cryptography stalwarts like the discrete log assumption or factorization hardness, zkSNARKs security is based on variants of the Knowledge Of Exponent (KEA) assumption for bilinear groups (instantiated via certain pairing-friendly elliptic curves). KEA is much newer and is also subject to criticism. Some experts believe the cryptography behind zkSNARKs to be relatively weak.

Zerocash is also highly complex and has been described as ‘moon math’, meaning that only a handful of people can properly understand and audit it and even can be challenging to spot bugs to its complexity. In fact, with the Zcash counterfeiting bug, the following was quoted:

- Discovery of the vulnerability would have required a high level of technical and cryptographic sophistication that very few people possess.

- The vulnerability had existed for years but was undiscovered by numerous expert cryptographers, scientists, third-party auditors, and third-party engineering teams who initiated new projects based upon the Zcash code.

This is effectively a form of ‘security through obscurity’. Lelantus, Lelantus Spark, RingCT and Mimblewimble constructions in comparison are much easier to understand.

Another drawback of Zerocash in its original form, the generation of a private transaction takes significantly longer than any of the previous privacy schemes approaching a minute on a powerful computer and much longer on slower systems while requiring several gigabytes of RAM. This resulted in very few people using its privacy features and also may exclude less powerful systems such as mobile devices. Zcash has made substantial improvements on this in their latest Sapling upgrade through the use of new BLS12-381 curves bringing down generation time down to several seconds and requiring around 40 mb of memory making it finally feasible for mobile devices.

Zerocash offers the highest theoretical anonymity and excellent performance but requires a complicated cryptographic construction, trusted setup, the use of new experimental cryptography and computational complexity when creating private transactions.

Electric Coin Company has recently produced a modification to the Halo proving system called Halo 2 that it intends to deploy to the Zcash codebase and network, along with a compatible transaction protocol called Orchard. Compared to the existing Sapling protocol (which uses a different proving system), Orchard on Halo 2 removes the need for a trusted setup process. Benchmarks on testnet code indicate that performance would be slower than Sapling-based zkSNARKs but remain highly competitive. The Halo 2 and Orchard implementations are licensed under BOSL, that does not allow third parties to use the Halo2 code until after the grace period expires.

While the original Halo proving system came equipped with a traditional academic-style preprint, we do not know of any corresponding literature for Halo 2 that is publicly available. The latest audit done by QEDIT also commented that unlike Sapling, Orchard does not have an overarching proof of security or a high level sketch of the proof yet. The audit also commented that reviewing such a complex system and its implementation is challenging and that many components of the protocol remain not well documented. The Orchard protocol with a Halo 2 proving system is a promising new development but remains a very complex construction that will take time for the wider technical and academic community to vet and understand fully. Combined with a more restrictive software license and less than complete documentation, anyone that uses Orchard or Halo 2 would need to trust and rely on the Electric Coin Company for its security or develop significant parallel resources to develop it independently.

Mimblewimble

As used in: Grin, Beam, Litecoin MWEB Sidechain, MimbleWimble Coin

Pros:

- All amounts are hidden

- Simple lightweight cryptographic construction

- Hides transaction amounts

- Blockchain can reduce in size as it only retains UTXOs

- No re-use of address problems

Cons:

- Monitoring the network can reveal details as to how the transactions are joined meaning the transaction graph is revealed

- Does not break transaction links, merely obscures them, hence a ‘decoy’ model.

- Vanilla Mimblewimble needs interaction between receiver and sender. Cannot post address and receive. Multi party transactions are problematic as all parties need to communicate to create a transaction. David Burkett’s one-sided transactions solves this but is only implemented in Litecoin’s upcoming MWEB sidechain. Beam uses SBBS and/or one side payments which comes at the cost of some privacy.

- If a block doesn’t have many transactions, anonymity is significantly reduced since it relies on other transactions to join with. Beam introduces additional decoys outputs if needed if insufficient transactions happen but remains unclear how much this improves privacy

- Cold storage in hardware wallets are tricky to implement

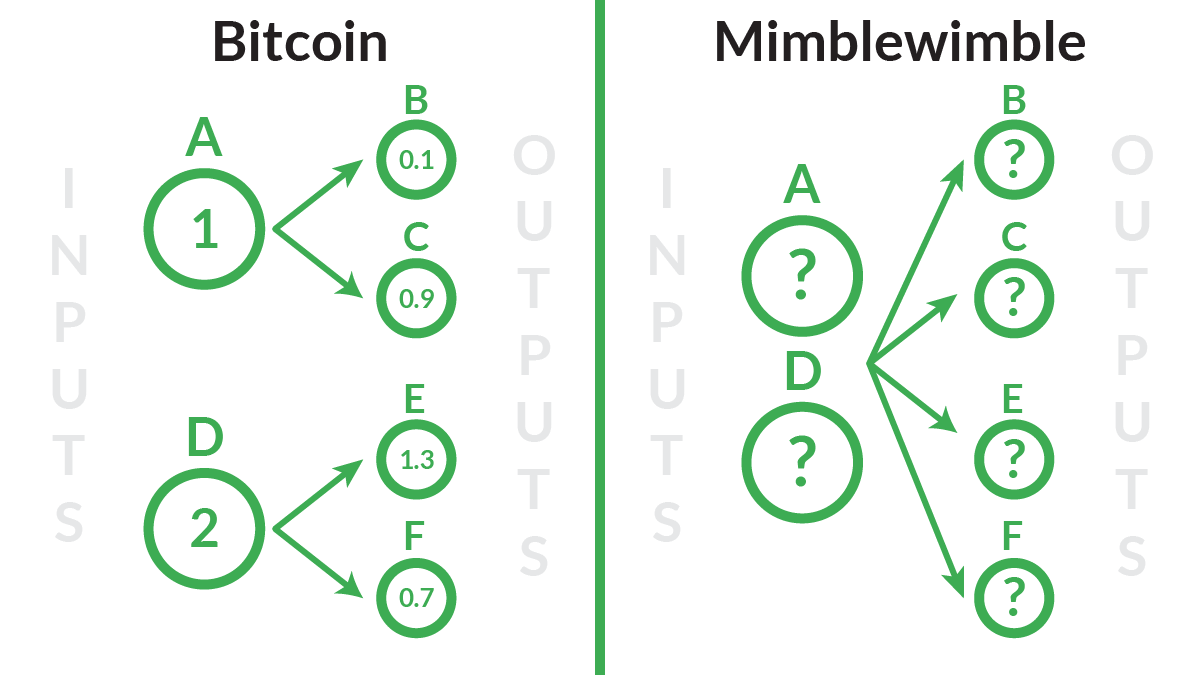

Grin and Beam are both implementations of MimbleWimble. Mimblewimble works via two primary methods, by hiding all transaction values and secondly by aggregating all transactions into one big transaction so that in a block, it appears as a giant transaction of many inputs with many outputs. Just looking at it from the blockchain alone, you can only guess which outputs came from which inputs provided that there are a few transactions in the same block. Mimblewimble also allows another feature called cut-through whereby if A pays to B who then pays it entirely to C, the blockchain can record A to C without even showing B.

An easy way to imagine this is comparing how transactions look like in Bitcoin vs how a transaction looks once it’s aggregated in Mimblewimble.

Imagine A sends to B and C. In a separate transaction D sends to E and F.

In Bitcoin this would be seen as

(Inputs) A > (Outputs) B, C

(Inputs) D > (Ouputs) E,F

They would also have transaction values further making them unique.

In Mimblewimble, all transactions values are hidden and these transactions are aggregated so once the transactions are joined in the block it will look like:

(Inputs) A, D > (Outputs) B, C, E, F

Now it is unclear who sent to who!

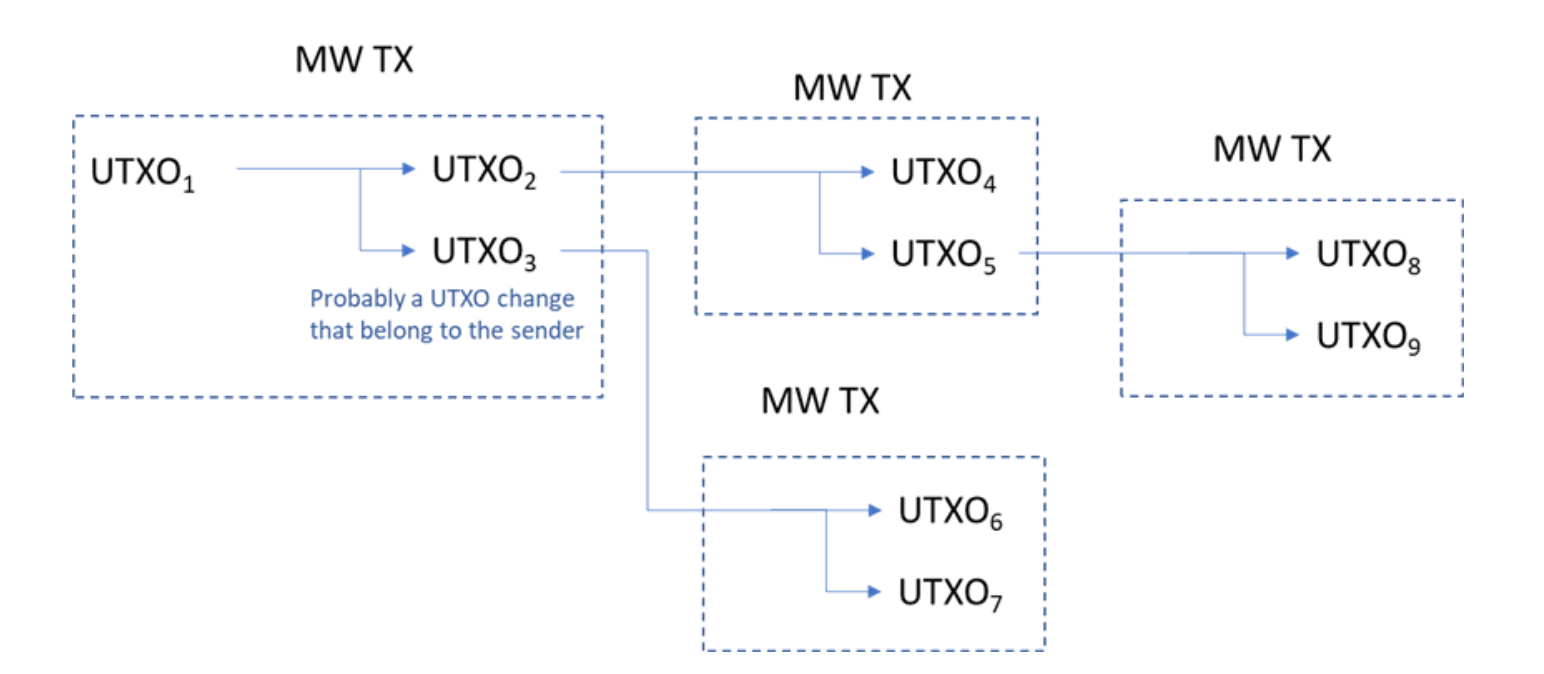

However the big assumption is that no one is monitoring the network as these transactions propagate and before they are recorded onto the blockchain. With vanilla Mimblewimble, someone could create a malicious node that connects to all other nodes in the network and record the transactions before they are combined together. This completely reveals the transaction graph.

To mitigate this, both Grin and Beam use Dandelion++ technology which changes the way transactions are propagated. Instead of broadcasting each transaction to all peers, the transaction is first sent through a series of randomly selected peers (stem phase) and only then diffused to the entire network (fluff phase). Each succeeding node rolls a dice to determine whether to continue the stem phase (90% change) or switch to fluff phase (10% chance). While the transactions are in the stem phase, they are also joined together with other transactions before being broadcasted widely. In theory, this makes it harder for a node to have a full picture of how the transactions are joined together.

In practice, the use of Dandelion++ doesn’t mitigate this sufficiently. A 2019 study showed that with a specially configured node, the researcher was able to uncover the senders and receivers of 96% of Grin transactions in real time even with the existence of Dandelion++. Beam’s implementation does make this harder by introducing decoy outputs when needed in the dandelion stem but it remains to be formally analysed to see how much practical privacy it adds.

This combined with the fact that Mimblewimble is also a decoy-based system similar to Cryptonote (although it achieves it using different methods), it still suffers the same drawbacks as other ‘decoy’ based privacy systems where repeated transactions can further reduce the anonymity as taint trees still remain. Additionally, if there are not many transactions in a block, this reduces privacy greatly while Beam’s implementation of MW attempts to mitigate this by introducing decoys where needed. As explained before, active monitoring of the network can dilute this even further.

Example of a transaction graph that can be built by tracing the MimbleWimble transactions.

Example of a transaction graph that can be built by tracing the MimbleWimble transactions.

A big drawback of traditional MimbleWimble is the need for interaction between the receiver and sender (meaning the receiver and sender need to communicate directly to communicate a blinding factor) and a massively different scheme that does away with addresses. This means you cannot just post an address on a website and have to give a new value all the time. This also complicates multi party transactions, for example A sending money to B, C, D, E in one transaction would require each of these parties to communicate to A before the send can happen. Beam’s implementation addresses this through the use of a Secure Bulletin Board system which allows people to post their messages to Beam’s full nodes so that the blinding factor can be communicated once the user comes online though further research is required if this leaks any information.

Another more neat approach is David Burkett’s one sided transactions that is being implemented in Litecoin’s Mimblewimble Extension Block sidechain that removes the requirement for interactivity.

Also although there are no addresses, the Pedersen commitments are still unique and therefore on its own MimbleWimble does not hide the transaction graph meaning you can still see how the funds flow, and thus can be considered ‘one time’ addresses. This means that without the added workarounds of Dandelion and Coinjoin, Mimblewimble’s privacy is equivalent to Bitcoin except that addresses are only used once and transaction values are hidden.

With full hidden values, Mimblewimble doesn’t have supply auditability as it relies on Bulletproofs/Confidential Transactions to check whether any additional coins have been created out of thin air. However the cryptography behind it is well understood.

Evaluating Other Privacy Schemes and Why Isn’t My Favorite Privacy Coin Featured in This Article?

All of the blockchain privacy schemes listed here are well reviewed by researchers and the concepts well understood. However, there are many coins in the privacy space but only a handful that really protect it.

For example coins such as Verge or DeepOnion do not have any onchain privacy mechanisms to hide the transaction graph or the amounts transacted and only have stealth addresses that prevent address re-use and TOR/i2p integration that only prevents your IP address from being associated to a transaction. Identical levels of privacy can be obtained by using Bitcoin through TOR/i2p and using new addresses making their claims that they are “privacy coins” spurious.

These are the key factors when coming across a new privacy mechanism:

- Does it offer privacy on the blockchain? Some privacy coins market themselves as providing privacy but completely don’t offer any onchain privacy. Protecting your IP address/TOR alone is insufficient.

- Is the privacy mechanism written by experts and reviewed? Read to see if their privacy scheme was vetted by cryptographers and has academic papers referencing it! Many are just cooked up by developers or programmers without any history in cryptography or information security. The technologies implementing privacy technology are generally not easy and even world class cryptographers make mistakes.

- Is it merely a rebrand of existing technology? Some projects rename existing privacy schemes with their own names and pass it off as their own. This is acceptable if they disclose the original privacy technology behind it.

- Does it involve centralized trust? If a privacy scheme that relies on you to trust someone else to protect your privacy, it is generally a poor privacy scheme. This covers some pseudo privacy coins that use centralized mixers.

- Does the team understand the cryptography behind these schemes? This is hard to determine unless you’re an expert yourself. Check their team to see if there is anyone with cryptography credentials or experience on their team.

Summary

Every anonymity scheme has its own sets of benefits and trade-offs, and we believe that continuous exploration and research of these privacy schemes can only serve to improve blockchain privacy as a whole. We at Firo strongly believe that Lelantus and Lelantus Spark compares very favorably to other anonymity schemes by providing a very well-rounded anonymity package, giving very strong anonymity using proven cryptography while remaining scalable and optionally auditable.

We hope this article gives you a much better understanding of how various privacy tech works on the blockchain.